Chandni Chowk — and why it still matters

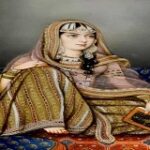

Candni Chowk isn’t just a bazaar; it’s a living chapter of Delhi’s Mughal-era planning, a marketplace that has shaped the city’s social and commercial life for nearly four centuries. The short answer to “Who made Chandni Chowk?” is: it was established in the mid-17th century under Emperor Shah Jahan and designed and laid out by his favorite daughter, Princess Jahanara Begum.

But that one line hides a richer story about urban design, imperial taste, commerce, and continuous reinvention.

Origins: Shahjahanabad, Shah Jahan and Jahanara Begum

When Shah Jahan decided to shift the Mughal capital from Agra to what is today Old Delhi, he founded a new fortified city — Shahjahanabad — with the Red Fort as its fulcrum. The planning of this new capital (around the 1630s–1650s) included ceremonial avenues, residential quarters, mosques and markets. The main commercial thoroughfare was conceived as an elegant boulevard with shops on either side and a water channel running down its centre so that, by night, the pool and channels would reflect the moonlight — hence the name Chandni Chowk (literally “moonlight square”). The market’s layout and the idea of the reflective water feature are widely attributed to Princess Jahanara Begum, who acted as the social and cultural matriarch (Padshah Begum) of the new city and played a leading role in several urban projects.

Design and early character

The original Chandni Chowk was not a random jumble of stalls but a carefully planned set of bazaars. Sources describe a half-moon-shaped square with a central pool and a shallow channel fed from the Yamuna that ran along the market. Streets were wide by contemporary standards, with shops arranged in orderly rows; the bazaar was reportedly some 40 yards wide and 1,520 yards long and housed over a thousand shops. Each lane (gali) often specialized in particular trades — an early example of functional urban zoning: silversmiths, cloth merchants, spice sellers and food artisans each had their own stretches. This order made Chandni Chowk a premier commercial artery in Shahjahanabad and later in colonial Delhi.

Social and ceremonial role

Chandni Chowk was also civic theatre. It was the route for imperial processions, a place for public gatherings and a visible expression of Mughal courtly life. The marketplace sat between the Red Fort and important religious and public buildings, which amplified its importance. Over time, this proximity to seats of power made it both a commercial hub and a stage for civic ritual processions, religious festivals, and public announcements threaded through the lanes and uares.

| RICKSHW PULLERS | FAMOUS SUNEHARI MASJID |

|

|

|---|

Changes under later rulers and the British

Urban features changed with political shifts. The original pool at the centre was gradually replaced (histor accounts point to a clock tower—Ghantaghar—taking its place by the late nineteenth century), canals were filled, and the area evolved under Mughal decline and British colonial rule. The 1857 uprising and its suppression altered property and demographics; many buildings were damaged and the market’s social fabric shifted. The British added their own civic architecture (including the Delhi Town Hall) and reorganized certain services, but the bazaar’s essence as a bustling market remained.

The marketplace through the centuries

What makes Chandni Chowk remarkable is continuity with adaptation. It retained long-standing trade specializations (spices, jewelry, textiles, sweets and street food), and its narrow bylanes continued to house traditional crafts alongside new commercial needs. Landmarks such as Paranthe Wali Gali, Dariba Kalan (silver), Kinari Bazaar (lace) and Khari Baoli (spice market) emerged as names identifying whole trades and communities. Migratory waves, partition, and urban growth brought new customers and vendors, layering more histories onto the lanes.

Architecture and built form

Architecturally, the area features a mix of Mughal-era residences, havelis, shops with jharokha-style facades, colonial additions and dense, informal structures added across the 19th and 20th centuries. Narrow galis open into small courtyards and shopfronts; above the shops are often residential quarters. This vertical mixing of uses—living above commerce—has allowed the market to function round the clock and sustain a dense urban economy. Preservationists have argued that the original aesthetic and the streetscape deserve careful restoration rather than sweeping modern interventions.

Modern challenges and conservation

Today Chandni Chowk faces the usual pressures of old urban cores: congestion, pollution, encroachment, infrastructure strain and the need to balance heritage preservation with livelihoods. Delhi authorities and heritage organisations have, at different times, attempted interventions — from traffic restrictions and façade restorations to heritage trails — aimed at making the area more visitor-friendly while protecting its living economy. These efforts raise complex questions: how do you restore a 17th-century waterway or pool in a fast-moving 21st-century market without displacing hundreds of small businesses? Recent redevelopment projects have tried to reintroduce visual order (improved signage, cleaned façades and pedestrian zones) while keeping sellers in place.

Cultural resonance: more than just shopping

Chandni Chowk is also a culinary and cultural map. Certain foods and festival practices are associated with particular lanes; shops that have been run by the same families for generations archive culinary, craft and oral histories. Pilgrims, tourists, students and local shoppers all pass through, ensuring that the market is not a sterile museum but a living, noisy, fragrant artery. Its presence in literature, films and oral memory keeps it continuously relevant as a symbol of Delhi’s layered past.

Why the maker matters

Knowing that Jahanara Begum — working under Shah Jahan’s patronage — planned Chandni Chowk is more than a trivia point. It underscores the role of intentional urban design in Mughal capitals, the agency of women patrons in courtly culture, and the long view that historical planning can offer modern cities. The “maker” in this case represents a set of ideas: ordered markets integrated with waterways, processional vistas connecting power and commerce, and an urban scale meant to impress as much as to function. The centuries since have altered the physical features, but the core idea of Chandni Chowk as a central civic-market spine remains profoundly intact.

| CHANDNI CHOWCK WAS MADE BY JAHAN ARA BEGUM ON PATRONAGE OF MAGHAL EMPEROR SHAH JAHAN | |||

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|